There’s a reason for all those jokes about gears and goggles, you know.

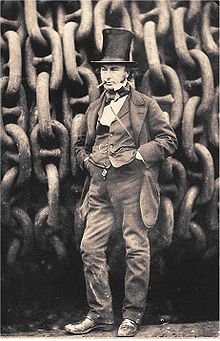

I can think of few subcultures so readily identified by a preoccupation with accoutrements. Steampunks love their stuff. Without it, they would be just another group of science fiction fans with some catchphrases and T-shirts to help identify one another. But visit any sci-fi and fantasy convention today and you’ll find numerous attendees wearing top hats, goggles, leather harnesses, and complex magnifying glasses, all identifying the wearers as devotees of steampunk.

The steampunk community grew out of an enthusiasm for Victorian-inspired science fiction literature like Neal Stephenson’s The Diamond Age and Gibson and Sterling’s The Difference Engine, as the aesthetics of those novels took on a life of their own. Steampunk might have become another quiet sci-fi fandom were it not for how powerfully these aesthetics inspired readers. Indeed, the modern steampunk community is in many ways more fashion movement than literary audience, a fashion movement with a heavy do-it-yourself attitude. What distinguishes steampunk from most other subcultures, though, is its passionate devotion to form married with function rather than following or dictating it—or at least the appearance of such.

It is this enthusiasm for customization and personalization that makes steampunk such an engaging fandom. Whereas other groups are content to purchase the mass-produced items that are aimed at them, like replicas of phasers and lightsabers, the steampunk community prefers less overtly commercial trappings. This is not to say that steampunks turn their noses up at commercially produced goods; many of the common elements of the steampunk costume are only available as such. It’s the eagerness to alter those mass-produced items as necessary that is an essential part of the genre. Goggles are ubiquitous among steampunks, and considering the relatively limited source of the items, it’s astonishing to see the variety of modifications that are made. Many—perhaps most—steampunks would prefer an entirely artisan-crafted ensemble, but lacking the funds for such extravagance they do what they can to make their wardrobes as uniquely their own as possible.

The compulsion for a more satisfying ownership of material items seems like a natural reaction to the prevalence of consumer goods in the twenty-first century. The most compelling and world-changing devices of the West have increasingly small physical profiles. The impact of the digital age upon our lives is incalculable, and the items we use to interact with huge portions of our world are vanishing nearly before our eyes. It seems logical that some of those most affected by devices would instinctively look back to the time of the rise of mass-produced goods and the dawn of classical modernity: the Victorian era.

The Victorians had their own obsessions with their objects. The late 19th century was the last time in the industrialized West that it was still common for the majority of clothing and furniture in a middle-class or upper-class household to have been handcrafted. It was readily apparent to critical observers that mass production would rapidly change this, and the genteel Victorians reacted with an understandable mixture of wonder and horror.

Interestingly, even some mass-produced items of the period bear purely aesthetic touches, like stamped motifs in metal girders. These affectations may well have seemed tacky to some at the time, but they undoubtedly helped acclimate the public to the impersonal sameness of architecture, furniture, and other objects found in day-to-day life. Viewing those items from the present day grants them the beauty of passed time possessed by many antiques but Victorian relics are often fashioned from extremely durable materials. They often relied on over-engineering to overcome limitations that we have since addressed with complex alloys or equations that would have been beyond their capabilities.  The Victorians simply built to last, granting many of their consumer products unthinkable lifespans when compared to most modern goods and many architectural materials. It is precisely the durability of the 19th century’s products that creates such an undeniable appeal to we who have come to view even unthinkably sophisticated devices as utterly disposable.

The Victorians simply built to last, granting many of their consumer products unthinkable lifespans when compared to most modern goods and many architectural materials. It is precisely the durability of the 19th century’s products that creates such an undeniable appeal to we who have come to view even unthinkably sophisticated devices as utterly disposable.

Living as we do in the aftermath of the Victorian era’s industrial and colonial detritus there is a deep appeal to looking back on those times through sepia-tinted glasses. Steampunk provides a uniquely satisfying opportunity for individuals to exert a personal influence upon the consumer goods which inundate their lives. Costumes and clothing for steampunk themed conventions are only the most obvious manifestations, but many have taken the aesthetic into their day-to-day lives. Few members of the fandom have resisted the urge to drool over Datamancer’s gorgeous steampunk-themed laptop computer casings. Like most modern electronics the internal components of these laptops may be disposable, but the casings are artisanal works worthy of preservation. There is real value in having a tangible and beautiful encasement for that arguably priceless data; such attention to external aesthetics suggests that the digital contents, the work and social data of so many of our lives, are equally valuable.

As beautiful as Datamancer’s work is, for many steampunks the real value of their things is less informed by the level of artistry and materials than by the level of personal expression and customization. Many devotees would find it far preferable to own a more modest piece they created themselves, and the community embraces tha “DIY” attitude at every level. Steampunk Magazine, for example, has published several tutorials of antiquated techniques for those who are interested. Their first issue offered an excellent beginner’s guide to electrolytic etching, undoubtedly to the chagrin of the parents of some enthusiastic teenangers.

Such personal involvement in the creation of an item leads to a sense of ownership far more authentic than that of the simple consumer. It is this engagement with their possessions that I find so fascinating and encouraging about steampunk as a subculture. Steampunks don’t just buy their stuff; they make it their own. This suggests to me that while it may currently be unfeasible to reject the capitalist trappings of modernity, compromise may be possible. I’m curious to hear what others think about balancing DIY ideals against affordable mass produced items in steampunk aesthetics. How best can the community be true to those ideals without being overly exclusive to newcomers?

It’s a tough question but I think we can all at least agree that goggles look rad as hell.

Simon Berman is a professional game writer, developer, and social media director. Somehow, Mr. Berman has managed to trick a number of people into paying him to write about wizards and zombies for a living. Mr. Berman lives in Seattle where he presently works as a staff writer for Privateer Press’ award-winning WARMACHINE and HORDES miniature combat games. His evenings are spent writing for Unhallowed Metropolis and working on several as-yet-unpublished, but very weird personal projects.